The bluegrass jam is a fundamental part of traditional bluegrass music. Surviving nearly 100 years, read how history and culture led to this surviving and enduring American tradition.

By Theresa Hawes

The Monthly Jam

The sun is setting on the All Souls Unitarian Church as a handful of people trickle into the church lobby carrying an assortment of acoustic instruments. First walks in a banjo player, then fiddler, followed by a few guitar players and a mandolinist. It’s the monthly Black Rose Acoustic Society’s bluegrass jam which takes place every 4th Thursday evening in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Musicians of varying skill levels, ages, backgrounds and creeds gather to take part in the gathering and community embodiment of Americana music. As the musicians arrive, they begin tuning their instruments and collecting any essentials such as picks, bows and “cheat sheets” or tablature from their cases. The church lobby, which is ordained in religious motifs and high ceilings, is the ideal acoustic space for these musicians to showcase their talent and prowess.

One by one the bluegrass jam attendees take their seats and a slightly oval circle begins to form in the church hall lobby. The guitar player kicks off the jam, “Let’s play Blue Ridge Cabin Home,” says a middle-aged man in a soft but commanding tone. The group nods with approval and the jam leader, a woman in her 60’s with a fierce presence and a mandolin hanging from her shoulders, alerts the group, “that we’re in the key of G.” Without hesitation, the 13 or so individuals begin to play in unison while singing the lyrics Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs made popular in 1955 with their Foggy Mountain Boys. “When I die, won’t you bury me on the mountain,” The tune reverberates throughout the main church hall. “Far away, near my Blue Ridge mountain home!”

While bluegrass music may be a departure from the religious hymnals that are typically played on Sunday mornings in the All Souls Unitarian Church, the monthly bluegrass jam provides a sort of spiritual experience in itself. Since the dawn of time, people have been coming together to make music. Whether it be a way to bring community together or celebrate a successful harvest, music has always been at the forefront of human identity; it has been connecting people since its genesis. Brandon Johnson the Program Manager for the Blue Ridge Heritage Area, an organization focused on connecting people to traditional music in North Carolina explains, “Music is like an ocean. It’s massive. It includes all types of fish, tributaries but everyone understands the ocean. Music is a universal language….And when you play music with people you love it doesn’t get any better.”

The Jam: A brief history

To the non-musically trained ear, the All Souls Unitarian Church bluegrass jam sounds like a professional quality show. The musicians are on key, in synchronized rhythm and taking turns sharing leads or “taking breaks”. People are singing in harmony and no one seems to be hogging the spotlight or messing up (too much). One might even think, “it must be rehearsed!” Despite sounding like a professional group, the jam is almost completely improvised. On any given bluegrass jam, one will never know who might show up and what songs from the “bluegrass canon” could be sung. The jam is spontaneous yet open, as long as you can understand its rules and your place.

The term “jamming’’ is decades old and has often been applied to denote the improvised interactions between and among musicians. According to the online columnist and journalist Evan Morris, creator of the Word Detective, a digital column examining the origins of English words, the original use in the context of improvised music for the word “jam” appears to have been used since at least the 1920s to describe the musical phenomena of collaborative improvisation in the jazz scene. He writes, “this usage, which dates back to 1920s jazz, may be using the “pile on” or “pressure” sense of “jam” to describe the effect of many musicians playing together without a score. Or it may be invoking the use of “jam” in the “jelly” sense to mean “something sweet; a very nice (musical) treat.” Regardless of its coinage, jamming is an integral part of American music especially within the bluegrass community. Which begs the question, where exactly did the bluegrass jam originate from?

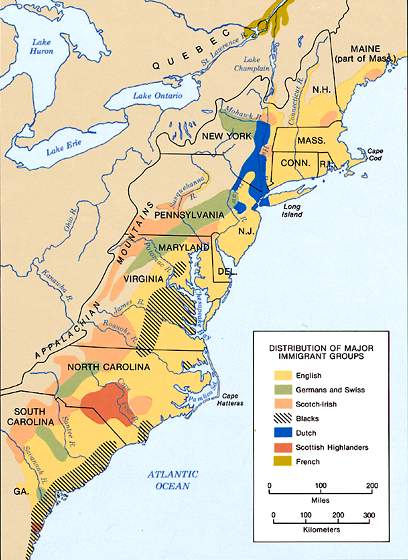

The story begins with the colonization of the Americas, specially in the Eastern region of the United States. Scot-Irish immigrants arrived to the rural enclaves of western Virginia carrying with them violins, while enslaved Africans brought the banjo from their homeland to the plantations in the south. The English settled up and down the 13 colonies and brought with them their ballads and culture. Nina Kümin, a Ph.D. candidate in music performance and baroque improvisation at the University of York explains how improvisation was a fundamental component to English music in the 1600s,“One of the main forms of music making for English [middle] society in the seventeenth century was consort music. Small groups of families, friends or neighbours would gather to play music together in several parts….Of this music making, one of the most elusive traditions was that of playing ‘divisions’. This was the practice of adding florid ornamentation to printed music and improvising variations (making them up on the spot) taking inspiration from a popular printed theme.”

Later, German luthiers who were renowned for their craftsmanship, such a Christian Friedrich “C. F.” Martin, founder of C. F. Martin & Company introduced new models of the guitar to the Lehigh Valley in Pennsylvania which would later include the famous steel string guitar. Eventually, mandolins circulated the rural Appalachian landscape as they became a cheaper second-hand alternative to guitars which were beginning to gain popularity especially in the 1930s. Families’ passed these heirlooms down to their children along with traditional folk tunes and their ways of life. As European settlements sprang up and down the Appalachian region of the United States, the geographic isolation of the region enabled the distinctive styles of music to remain largely intact and embedded in local culture. Towards the end of the 1800s, with the emergence of accessible transportation networks such as railroads and recorded music, Appalachian music began to blend that tradition with vaudeville music, African-American styles, and Minstrel Show tunes. Many refer to this phenomenon as “Old Timey” music and a precursor to modern bluegrass.

At the turn of the 20th century, despite early recorded music beginning to make its rounds in the United States, live music was still the number one form of entertainment, especially in geographically isolated regions. In the hollers of Kentucky and up and down the Great Smokey Mountains, Appalachian folks utilized traditional folk music and modern influences to create live entertainment. It should come to no surprise that this style incorporated the many acoustic instruments their ancestors and great ancestors brought with them to the United States. From porch gatherings to Barn dances, musical gatherings (often improvised) became the standard in live entertainment in the Appalachian region prior to the 1950s. “Before in small communities it was the THING!,” explains Colorado bluegrass musician and bassist Joy Maples. “It was where everyone came together on Sunday afternoon. People gathered to play to sing the bitterness out of their souls. It was these farmers with hard lives up and down the Appalachians. It was a way for you to escape your life.” Michael Watry, a self-proclaimed Bluegrass Jambassador and board member of the Black Rose Acoustic Society, adds, “I see it as something that comes from a more rural social time in America. It is a musical form that came from Appalachia. This was music that was shared orally and people learned songs by listening and learning. It was passed on from generation to generation.”

The Jam Rules Matter

Back at the All Souls Unitarian Church, the boisterous jam leader turns to the next member of the Black Rose Acoustic Society’s bluegrass jam circle with a stern nod signaling “they’re next in line” to solo the melody of Blue Ridge Cabin Home. The dobro player doesn’t have it so he shakes his head. The jam leader immediately shouts, “Fiddle! Go!”. The fiddle player leaps from his seat and starts methodically pressing the bow up and down the instrument’s neck. A creative melodic tone engulfs the circle and everyone else plays rhythm. “G….C…D…G…!,” declares the jam leader indicating which chord is to be played. The variation of skills levels prompts a cue as a reminder. The 13 or so folks like what they hear and suddenly a few “Yeehaws!” emerge. Smiles press across everyone’s’ faces. The vibe is fun, spirited and lively. Not a single jam musician appears to be having a bad time. However, the vibe of the jam is only as good as the rules which govern it.

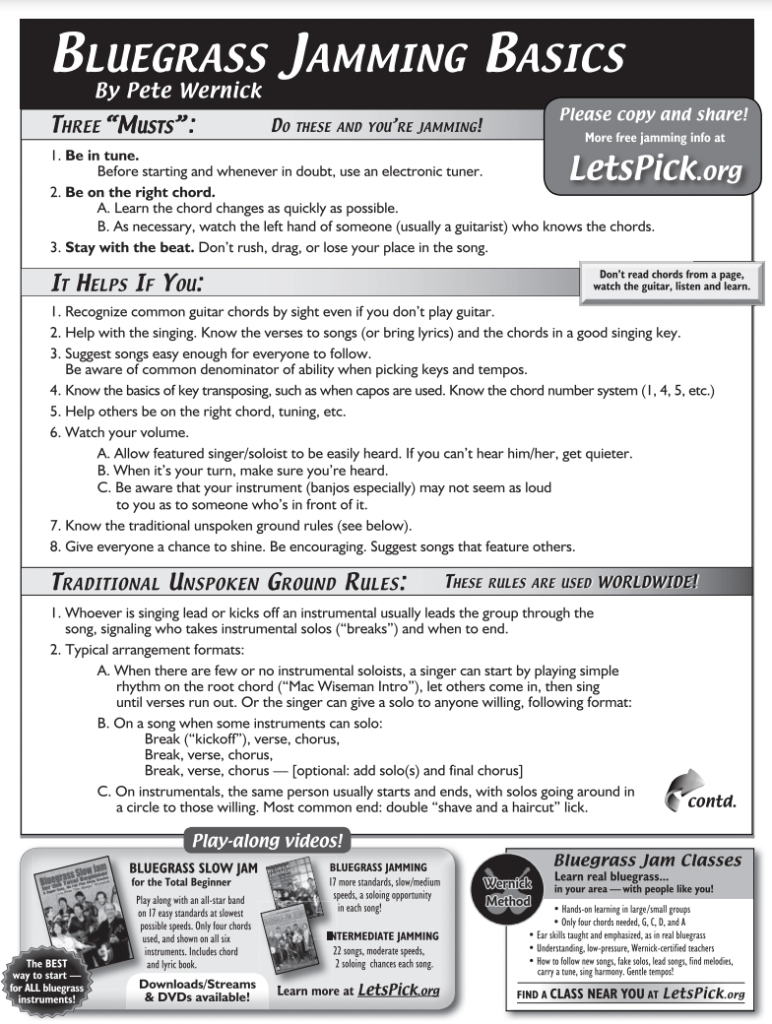

Like most bluegrass jams, the Black Rose Acoustic Society abides by a set of spoken and sometimes unspoken “rules” or “norms”. Firstly, members of the jam sit in a closely knit circle. Secondly, instruments are expected to be tuned correctly and remain in tune. Thirdly, members are discouraged from taking solos out of turn. Fourthly, members are expected to keep time or be able to stick to the rhythm. Jambassador Watry summarizes the importance of this rule, “The rhythm is really what ties everything together. If you don’t have a good rhythm then people can’t fit together”. Finally and most importantly, jam members are expected to maintain an attentive ear and be listening at all times. Watry explains, “listening is probably the most important rule as it encompasses everything you need for a jam. You need to listen for the chord changes, listen to the dynamics, don’t drown out people. If someone is singing a verse you want to hear that story. It’s how you harmonize.”

“Bluegrass definitely has rules.” asserts Bluegrass Jamming expert Pete Wernick, musician and creator of the Pete Wernick Method. “While there’s some regional factors, the rules stay mostly the same….I’ve jammed in Ireland, Israel, Hawaii and even though the culture is different, bluegrass tradition is respected because there’s rules.” “We don’t teach the solo in the Wernick method. We teach the song, that’s a really important distinction. We’re all playing and singing, if you do well you’ll get a solo and play the melody. If you do well with that, you’ll get to take on a bit more. But the rules keep us together.” Bassist Joy Maples adds, “First of all it’s about the song. It’s about the music not about you. We’re all contributors. It’s really important to focus on the song. To be present in it. When someone else takes a lead, but if you’re fiddling with your own, there’s a real tendency to get loud. You should never be louder than the person next to you. That should never be the goal. Try to go down a notch. It’s about the music, not you. Just chill out and listen. Finally the former owner of the Jamshack and frequent bluegrass jammer Rob Tobiassian ads, “Do some homework. Learn a song, know the lyrics and keep it simple…Contribute!”

An Open Invitation

The clock reads 8:25 pm in the All Souls Unitarian Church on a cold and icy November evening. The Black Rose Acoustic Society monthly bluegrass jam has reached its conclusion for the evening. For the past 2 hours, individuals from all walks of life have been jamming away to Appalachian ancestral tunes and modern bluegrass hits. As a young 20-something-year-old dobro player gets up to leave, a middle-aged banjo player with a stocky build sporting a United States Marines T-shirt whispers across the room, “See you next time!” The dobro player responds with a brief smile, “I’ll be back! Tonight was fun!”

Before the attendees depart, Jammbassador Michael Watry informs the group of an upcoming holiday event. “Coming up in two weeks we have our annual holiday bluegrass jam. It’s a fun time. We have sheet music available if anyone is interested in learning some festive tunes.” Watry glances at a stack of folders with sheet and tablature music stacked about a foot high in the middle of an amoeba-shaped circle on the church lobby floor. While most bluegrass musicians train themselves to play by ear in order to avoid the reliance on sheet music and tablature, a few newbies need to examine the tunes as a refresher and grab a sheet. “Let’s see, what else,” Watry adds, scanning his mind trying to recall the information about the upcoming schedule. The 12 or so musicians listen intently readied for another night of community and camaraderie. As always, it’s an open invitation.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

- The Black Rose Acoustic Society Website

- Black Rose Acoustic Society Jam Schedule

- Pete Wernick Website and Class Schedule

- Blue Ridge Music Trails Website

- The Complete Bascom Lamar Lunsford Bluegrass Story

SOURCES

Allan, David. “A Highland Wedding.” National Galleries of Scotland, National Galleries of Scotland, http://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/8322. Accessed 10 Dec. 2023.

“Appalachian Music.” The Library of Congress, 1942, http://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200152683/.

“Brandon Johnson.” 7 Sept. 2023.

ChiTownSoundz, director. Duke Ellington Jam Session 1942 Jazz Soundie. YouTube, YouTube, 5 Mar. 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GAdCtSLBUps. Accessed 10 Dec. 2023.

Hoffman, David, director. The Complete Bascom Lamar Lunsford Bluegrass Story. YouTube, 13 Dec. 2014, https://youtu.be/B3M5dJl2SgA. Accessed 10 Dec. 2023.

“Jam Session.” The Library of Congress, 1942, http://www.loc.gov/item/mbrs00078987/.

“Jam.” The Word Detective, http://www.word-detective.com/2011/09/jam/. Accessed 3 Nov. 2023.

“Joy Maples.” 1 Oct. 2023.

Kümin, Nina. Jamming Together: Recreating Improvised Seventeenth-Century Musical Divisions, Middling Culture, 2021, https://middlingculture.com/2021/07/29/jamming-together-recreating-improvised-seventeenth-century-musical-divisions/. Accessed 10 Dec. 2023.

“Laura Boosinger.” 7 Sept. 2023.

“Library Homepage: Square Dancing in the Kentucky Foothills: 1940s: Renfro Valley, Berea High School, Street Dances, and the Estill County Mountain Square Dance Festival.” 1940s: Renfro Valley, Berea High School, Street Dances, and the Estill County Mountain Square Dance Festival – Square Dancing in the Kentucky Foothills – Library Homepage at Berea College, libraryguides.berea.edu/c.php?g=299390&p=1999869. Accessed 3 Dec. 2023.

“Michael Watry.” 28 Sept. 2023.

“Pete Wernick.” 17 Oct. 2023.

“Rob Tobiassen.” 3 Dec. 2023.